Nashetu-E-Maa

Practical Action

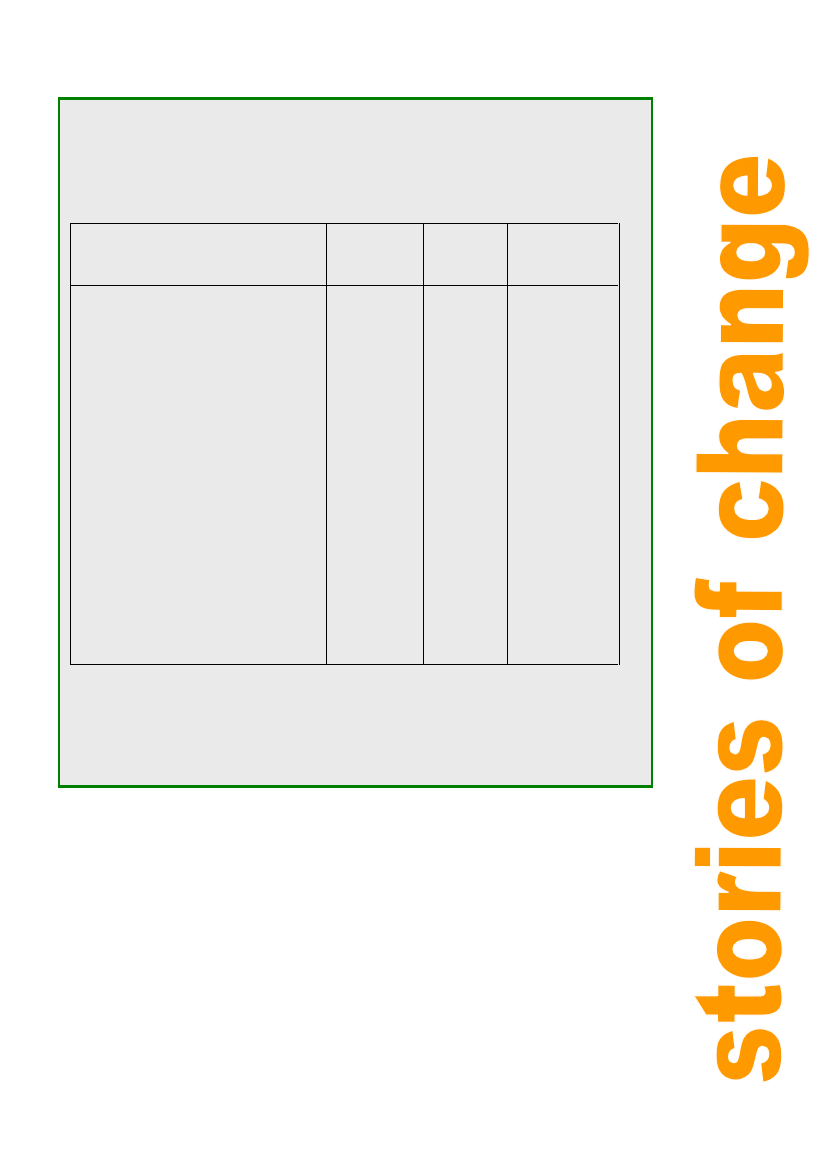

How costly is ‘affordable’?

Practical Action aims to increase access to affordable shelter but what is affordable to one is

expensive to another. The estimated cost of some of the technology options outlined above

are given below at 1999 prices, when the exchange rate was about 100 Kenyan shillings to 1

pound sterling.

Ferro-cement panel wall under G.C.I sheet roof: 3 roomed house.

Description of materials

Quantity

Unit Cost

(Ksh)

Total Cost

(Ksh)

GCI sheets

Building posts

Roof ridges

Chicken wire 6' x 1"

Ordinary Portland Cement

Roofing nails

Ordinary nails

Timber cypress 3" x 2"

Timber cypress 2" x 2"

Timber cypress 6" x 1"

Wood preservative

Door frame (external) T-door

Internal doors and frames (Batten)

Timber windows and frames 21/2" x 21/2"

Binding wire

Gloss paint

Undercoat paint

Sand

Hard core

Hinges 4"

Pad and tower bolts

20

35

5

2 rolls

35 bags

5 kgs

15 kgs

200ft

200ft

100ft

5 litres

1

2

4

3kgs

4 litres

4 litres

2 lorry loads

1 lorry load

9

6

310

120

150

3000

430

160

55

9

7

9

150

1600

1100

650

70

550

350

5,000

2,000

40

40

Costs

Labour

Total

6200

4200

750

6000

15050

800

825

1800

1400

900

750

1600

2200

2600

210

2200

1400

10,000

2,000

360

240

_______

61,485

15,000

76,485

Calculated in a similar manner a 3 roomed rammed earth house under GCI sheet roof costs

44,840 KES; a Stabilised Soil Block walled house under a GCI sheets roof costs 48,050; a

ferro-cement skin roof and walled house costs 47,675 KES. The addition of a ferro-cement

skin roof costs 15,210 KES whilst a water storage jar is estimated to cost 7,680 KES. These

costings will vary quite considerably, apart from variations in house size, costs incurred in

transporting materials to site can be a significant portion of overall costs.

So what? Project impact and sustainability

Having intervened in housing development and worked in partnership to develop new

technological options the Practical Action team has been considering the effect of its work and

has been asking what happens next, when the project ends. There are encouraging signs of

people’s increased ability to fund their own housing improvements and to take the initiative in

improving their built environment. During an impact study 9 out of the 28 project beneficiaries

questioned had built separate new kitchens and 8 had improvised guttering to improve their

rainwater catchment.

The capacity of women as individuals and collectives has developed considerably as the project

activities have progressed. The following are some of the benefits, which are now evident:

• the increased ability of women to fund their own housing improvements. The Naning’o

Women’s Group improved their houses in 1992/93. They were subsequently given a

blockmaking machine and have been producing blocks in order to build rental housing

on a collectively owned roadside plot;

15